Baseball artist Ronnie Joyner has savored the Triple Crown of success. Some artists must settle for getting published or paid. Joyner’s gone the extra base of sorts, reaping praise from those he depicts.

When the accolades come, none are taken lightly. Even after retirement, tight-lipped players remain men of deeds first, words second.

Joyner shared the experience of having baseball history as his teacher.

Q: How do you describe your work?

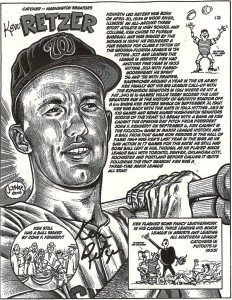

I don’t know what this type of art was technically called in its heyday (1920s-60s), but for lack of a better term I just started calling my version of this genre “bio-illustration”. I’d always admired the old newspaper legends of this genre — Thomas “Pap” Paprocki, Willard Mullin, Lou Darvas, Jim Berryman, Phil Berube, etc., etc., but I never thought I would have the venue (albeit it a smalltime venue) to bring it back on the scene. But POP FLIES gave me the opportunity, so I began creating a Brownie bio-illustration for each quarterly issue. Soon I was creating bio-illustrations of Senators, Braves (Boston) and Athletics (Philadelphia) players for their fans’ similar publications. Eventually I began creating a weekly bio-illustration for SPORTS COLLECTORS DIGEST (SCD. This was great because it allowed me to draw players from all teams and all eras. While I have illustrated a good number of mainstream and Hall-of-Fame players, I have always taken particular interest in illustration of lesser know guys.

No disrespect intended to the big-name guys, but I feel there are plenty of other avenues to learn about them, so I like to carry the torch for the little guys. Now I have drawn close to 200 guys, and my hope is that I will someday publish them all in a book.

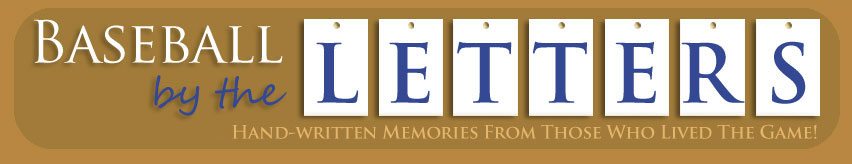

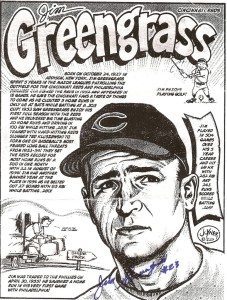

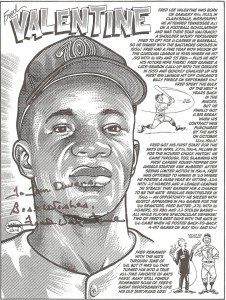

Q: I received photocopies of your bio-illustrations of Jim Greengrass, Fred Valentine, and Ken Retzer after corresponding with them through the mail. How do you feel about that?

A: That really makes me happy. I am truly honored that they choose to utilize my bio-illustrations to tell the story of their careers when they correspond with their fans. I will occasionally meet a player who I’ve previously illustrated — a guy who I’d not previously met. Sometimes when they put two-and-two together and recognize my name they’ll tell me that they received copies of my bio-illustrations in the mail from fans who clipped them out of SCD. That always makes my day. That reason alone often makes me prefer illustrating living guys, but every now and them I’ll dip back into the lives of deceased players for my subjects.

Q: Are you writing the great bios, too?

A: Yep, I write ’em and draw ’em. I’ve always enjoyed researching and writing, so this gives me an outlet for that passion. I occasionally write straight-forward article-type stuff, so my bio-illustration text allows me to ham it up a bit in the style of the genre — you know, lots of silly jargon like “swiped 20 bags,” “clubbed 20 round-trippers,” “fence-buster,” “port-sider,” etc., etc. One thing you may have noticed is that I always end EVERY sentence, even the most mundane of statements, with an exclamation point (unless the piece is particularly serious like that of Willard Hershberger, for example). That’s something I picked up from my comic book

reading days. I thought every one would get the joke, but I have actually had complaints about it from the occasional SCD reader.

Q: Have you corresponded with the retirees BEFORE a work is created? It seems most retired players will answer an interesting question if asked politely.

A: I have, in fact, talked with players before doing a drawing, but usually only if someone has asked me to illustrate someone obscure for whom it is difficult to find reference material. A couple of recent examples are Red Borom and Ducky Detweiler. Most of the time I just go at it on my own. I used to always send the players a batch of copies of my finished drawing AFTER completion, but I’ve done less and less of that these days due to being overly busy.

I never thought I’d see the day where I would forgo the possibility of a cool interaction with a player because I am too busy, but that’s sadly the case. When I do reach out to players by sending them copies, their reactions are, amazingly, mixed. There are guys who are very gracious and friendly, but there are also guys who seem to care less. And it’s not just the guys you’d think, either. Some times it may be a HOFer who is blown away, yet the unknown guy seems unimpressed. But usually it’s the other way around. Accolades from guys like Greengrass and Retzer, however, make it worth the time and effort to try and communicate to every guy.

Q: What kind of response do you get AFTER they see your work? This is like

the back of a great old Topps card. Even greater!

I don’t mean to dampen your enthusiasm too much, but it’s hard to impress most players. Even the most short-time player was usually great in all his seasons leading up to his major league experience. That means they all have stacks of scrapbooks (I’ve seen ’em!) loaded with clippings about their heroic baseball exploits. Many have already been depicted in illustrations like mine by the sports artists of their time. Or they’ve been on classic baseball cards. And many of the more well-known players I’ve illustrated have already been the subject of paintings/illustrations by well-known artists versus a no-name (it is what it is) like me. For those reasons, many players tend not to be bowled over

by yet another tribute to them.

That said, there are definitely enough guys out there who love what I do for them, and that makes it fun. 1945 A.L. MVP Eddie Mayo paid me the ultimate compliment by telling me my bio-illustrations were better than any baseball card could ever be because it captures the fun of a card, yet it’s much more informative. A quick look at a list of my drawings reminds me of some guys who have been very enthusiastic about my bio-illustrations of them: Rugger Ardizoia, Joe Astroth, Eddie Basinski, Bobby Bragan, Al Brancato, Joe Cunningham, Clint Dreisewerd’s family, Mike Epstein, Boo Ferriss, Ned Garver, Chuck Goggin, Eli Grba, Don Gutteridge, Spook Jacobs, Johnny James, George Kell, Al LaMacchia, Frank Mancuso, Hal Manders, Walt Masterson, Lee Maye, Brian McCall, Ralph McLeod, Dick Means’ family, Ed Mickelson, Al Naples, Bob Neighbors’ family, Herb Plews, Jackie Robinson’s wife Rachel, Bob Savage, George Shuba, Billy Southworth’s (dad and son) family, Virgil Trucks, Lon Warneke’s daughter, Bill Werber and Ken Wood.”

Remember how Joyner noted that he was a baseball autograph collector first? Tomorrow, he’ll divulge a few of his TTM misadventures with names you’ll know!